25 'Q & A'

Explore the Trail in Your Mind! (Then with Your Body!)

In 2017, Canadians commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Trans Canada Trail / The Great Trail (and Canada’s 150th year as a country!). Here are 25 questions and answers to help you learn more about the Trail. We hope you find them interesting and informative!

-

What is the Trans Canada Trail?

The Trans Canada Trail (recently rebranded “The Great Trail”) is the world’s longest network of recreational trails, joining the country together just as the Trans-Canada Highway did, though the Trail goes even further, including not only all ten provinces but all three territories as well.

The Trans Canada Trail / The Great Trail is a multi-use trail on which – depending on the location – you can walk, wheel, bike, ride a horse, ski, snowmobile, canoe, or kayak along its 20,000+ kilometres, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific and Arctic oceans. The Trail includes urban, rural and wilderness trails in every province and territory. In total, the Trans Canada Trail is comprised of around 500 individual trails such as the Galloping Goose Trail in BC, the Petit Témis in Québec, and PEI’s Confederation Trail, with majestic landscapes and scenic detours all along the way.

All in all, the Trail links Canadians in about 1000 communities, including all the provincial and territorial capitals. -

Why is the Trans Canada Trail the longest recreational trail in the world?

Canada’s Great Trail is the longest recreational trail on earth because Canada is huge – it’s the second-largest country in the whole world! – and the Trail stretches all the way across the country from east to west, and from the north to the south, for a total length (once completed) of nearly 24,000 kilometres. Just look at a world map – it would be amazing if this weren’t the longest trail in the world!

With only 35 million people spread across a huge country with a lot of challenging geography, Canadians have been able to accomplish this massive task through dedication and teamwork. It's amazing what you can achieve when you work together! -

When did the great adventure of the Trans Canada Trail officially begin?

In 1992, Canada celebrated the 125th anniversary of Confederation. At that time, the idea of a legacy project started to dance in the head of Bill Pratt, Canada 125’s General Manager. Under his leadership, the legacy project idea was presented to the Canada 125 Board of Directors and discussions began.

Among all the different legacy project concepts that were considered, the Trans Canada Trail (Pratt’s own favourite) was the one that stuck. The board decided to support the Trail project, and after several rounds of negotiations the federal government (under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney) approved and funded it. Federal funds helped establish the Trans Canada Trail Foundation to plan the Trail project across the country. The Foundation was established in early 1993 and the project was publicly launched in June 1994. And this was all just to get the project started! -

The Trans Canada Trail became the legacy project of Canada 125, an anniversary celebration of Confederation. What is Confederation? When did it happen? How many times has

Confederation been celebrated?

Though the story of Canada actually began much earlier, Confederation was the official beginning of Canada as a country.

On July 1, 1867, the British North America Act was signed by the leaders of three British colonies: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the United Province of Canada. The Act was then approved by the British Parliament and Queen Victoria. The three colonies became the first four provinces of the new Dominion of Canada: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Québec.

New provinces and territories gradually joined over the years until, in 1999 (132 years after the first act of Confederation), Nunavut was formed as a distinct territory and Canada was finally composed of all its current 10 provinces and 3 territories.

Confederation has been celebrated every year since the first official Dominion Day in 1879, though most of the celebrations until 1958 were locally organized. In 1958, the Government of Canada began to oversee nation-wide annual celebrations of Dominion Day (renamed Canada Day in 1982).

In addition to the annual celebrations, there have been six major celebrations of Confederation so far, including Canada 150 in 2017. The first major national celebration took place on the Dominion of Canada’s very first anniversary in 1868, and has been followed by national celebrations for the country’s 50th, 60th, 100th, 125th and 150th anniversaries. -

What had to be in place for the Trans Canada Trail to be born?

Many things had to be in place for the birth of the Trans Canada Trail. The following are a few of the main ones:

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney (1984-1993) was indirectly involved with kick-starting the Trans Canada Trail, as he gave the green light to the Canada 125 celebrations at which the Trail was founded.

The unfortunate resignation of original Canada 125 Co-chair John Bitove had a silver lining, as Canada 125 then brought in Frank King and, through him, Bill Pratt. Both King and Pratt were key to the creation of the Trail. King and Pratt had been centrally involved in planning the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics, and working at Canada 125 gave them another opportunity to serve their country. At Canada 125, with King’s support, Pratt became Co-founder of the Trans Canada Trail.

The Trans Canada Trail project was able to build on the thriving network of existing trails, trail volunteers, and trail organizations already in place across Canada – all of which set the stage for the TCT.

In the spring of 1993, the new project encountered a major hurdle, as its approval by the federal government was withdrawn. The Trail’s founding team asked for help from Fred Doucet, a longtime friend of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney who had worked closely with Mulroney for a number of years. The TCT team asked Doucet to communicate the Trail’s value to Mulroney or other top government officials. In a short time, the project was re-approved and initial funding of $580,000 was made available to establish the Trans Canada Trail Foundation. -

Why was 1992 the right time to kick-start the Trans Canada Trail?

The transcontinental railway was built across Canada to help bring more provinces into the country, and the Trans-Canada Highway was built to accommodate the automobile and to drive Canadians from one end of Canada to the other. Then came Canada 125, during which Bill Pratt and others began looking for a legacy project to make the anniversary celebrations more memorable.

The Trans Canada Trail was considered the best idea, as it was special for several reasons. For one thing, it was a third historic opportunity to link the country together – this time based on recreation and enjoyment of Canada’s natural and cultural character. Forging this new kind of cross-Canada connection seemed like a perfect way to honour the Canada 125 celebrations.

Pratt and his colleagues argued that the available combination of a nation-wide celebration, motivated individuals, and access to federal funds through Canada 125 made 1992 a perfect time to kick-start the Trail, as such an opportunity was unlikely to come again soon. -

Why did the Trans Canada Trail’s founding team think the idea was worth pursuing? What were the benefits and advantages that the Trans Canada Trail’s founding team recognized

in the Trans Canada Trail?

The following are a few of the big ones, but there were more!

Due to the work of more than 80 local trail groups and tens of thousands of trail volunteers, a network of trails and organizations was already in place across Canada. The TCT could build on these, linking them to form a national trail system. Further, the TCT could offer a strong, central voice for the evolving, Canada-wide trail movement, allowing local trail groups to have greater influence. The founders recognized that the Trans Canada Trail could offer many gifts to Canadians. The most obvious included opportunities for adventure, ways to stay fit, chances to get to know our natural (and urban) environments, and a quiet, eco-friendly way of getting around cities and towns.

Once established, the Trail, as the longest recreational trail in the world, could also become a popular tourist attraction for visitors from around the globe.

Other important benefits included economic gains through purchases of equipment, nearby lodgings and restaurants, etc., as well as community-building opportunities, as local trail users could meet each other on the Trail or even find ways to support the Trail together.

And finally, the Trans Canada Trail could foster a wonderfully humane, creative brand of patriotism, making Canadians proud of a national project based on positive principles such as mutual cooperation, dedication, creativity and compromise. -

In the story of the Trans Canada Trail’s birth, there was one founder, then two. Why? Who are they?

The main leader behind the Trans Canada Trail project was Bill Pratt, General Manager of Canada 125. At Canada 125, Pratt met Pierre Camu, Canada 125’s Director of Programs. Pratt asked Camu to join him in advocating for the Trail as a legacy project, and over the following months Camu became Pratt's principal ally. Later, to acknowledge Camu’s support and in recognition of the need for his continued participation, Pratt suggested that Camu be named the TCT’s Co-founder. Camu stayed on for several more years, despite his age (he was 69 when it began!) and his other projects.

Pratt and Camu were leaders by nature, and they loved to take on new challenges. Pratt came from Calgary to Ottawa to help plan Canada 125. Starting out in the construction industry, Pratt eventually became Chief Operating Officer of the Calgary Winter Olympic Games in 1988. As for Camu, he had acted as a Professor of Economic Geography at Laval University, as President of the St. Lawrence Seaway Authority, and as Chairman of the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), among other things. -

Did the idea of building the TCT just pop into the founders’ heads at Canada 125? Where did the idea come from?

NO, the idea for the Trans Canada Trail didn’t just pop into the founders’ heads!

In preparation for the Canada 125 celebrations, Canadians from across the country were asked to send proposals for projects to help mark the anniversary. This process led to the Trans Canada Trail concept. The founders’ vision for the Trail was spurred on by two proposals that came across the Canada 125 desks. One involved the further development of a section of the pedestrian-only National Hiking Trail, and the other was for a regional multi-use trail in Alberta. The Trans Canada Trail was conceived as a mixture of these two ideas (a national trail and a multi-use trail), and quickly became the most promising among Canada 125’s potential legacy projects. This was how the TCT was proposed as a national, multi-use trail for all Canadians. -

At the beginning of the Trans Canada Trail story, was it difficult to get the project approved? Did it have any opponents?

YES, it was difficult to get the project approved. And YES, the Trans Canada Trail project had opponents!

The idea of building the longest trail in the world was very exciting and attracted a lot of people’s attention, but at the same time the Trail’s founders had no detailed action plan, and no corporate sponsors were in place to support the Trail financially once Canada 125 wrapped up.

Further, the federal government’s mandate for Canada 125 was for a one-year anniversary celebration only, so funding a project that would take place after 1992 required a change of policy or a whole new agreement. It didn’t help that the Trans Canada Trail idea was introduced in the middle of the year, when the Canada 125 celebrations were already half finished and time to discuss this complex project was therefore quite short.

Some people at Canada 125 didn’t share the founders’ view that the Trail would be a perfect legacy project to immortalize the anniversary celebrations; some simply wanted to wrap up the Canada 125 celebrations and respect the existing mandate. The project’s opponents also had a legitimate question for the Trail’s founding team: “Is such a large, complex project even feasible?”

Even after the project was approved by the Canada 125 board of directors, several rounds of difficult negotiations between Canada 125 and the federal government followed. During the second half of 1992 and into early 1993, the Trail project was nearly rejected, then re-approved under stricter conditions, then definitely rejected, and finally approved once and for all. -

To make the Trans Canada Trail a reality, a foundation had to be established. What is a foundation? What is the purpose of the TCT Foundation?

A foundation is an organization established to oversee a major project. Foundations are often supported entirely or partly by donations. Funding for the Trans Canada Trail Foundation has come from a wide variety of sources, including millions of dollars donated directly by private citizens.

Established in 1993, the TCT Foundation is dedicated to overseeing the building and maintenance of the Trans Canada Trail / The Great Trail. To do this, the Foundation has built strong partnerships. Through relationships with governments, businesspeople, the general public, trail organizations, etc., the Foundation has been able to continue its ambitious task of overseeing a massive – and growing – national trail. -

Who runs the Trans Canada Trail?

To run a foundation, you need a volunteer board of directors, a paid staff, and, in many cases, sponsors and volunteers.

At the beginning, the TCT Foundation had a very small staff and a small number of board members. The project was new and profoundly ambitious, and it seemed unrealistic to many Canadians. However, as the project got bigger, the staff and the board got bigger as well, keeping pace with the growth of the Trail and therefore keeping the project viable.

Over the years, different people have held the top positions within the TCT organization, which now includes both the Trans Canada Trail Foundation (focused on fundraising) and the Trans Canada Trail Charitable Organization (focused on development at the local level). Board Chairs have included, to take four prominent examples, Bill Pratt and Pierre Camu in the early days and Paul LaBarge and Valerie Pringle later on. -

Who’s in charge of the Trail?

The question of who’s in charge is complicated to answer. The TCT Foundation is the national funding body for the Trail, and the TCT Charitable Organization oversees development at the local level, but neither the Foundation nor the Charitable Organization owns or operates any actual trails. Instead, through its provincial and territorial partners, the TCT organization consults on the construction, maintenance, and range of use of local trails whose operators have agreed to be part of the TCT route. Cooperation is voluntary, and trail organizations can withdraw from their association with the Trans Canada Trail if they choose to. Therefore, the TCT is not really their “boss.”

Trail sections are operated by local associations, conservation authorities, municipalities, and park authorities, often with input from provincial/territorial governments from whom they may also receive funding. Trail organizations, governments, or private landholders who have offered rights-of-way to the Trail are the actual owners of the physical trails.

In short, authority over sections of the Trail is a matter of ongoing negotiation, and the details look different in different places. This is part of what makes the Trail so extraordinary: it requires ongoing attention, consideration, creativity, and compromise among many parties with many different priorities. - Is it right to say that without all the trail volunteers, the TCT would never have been anything more than a pretty idea?

From the beginning, the members of the Trans Canada Trail’s founding team began to say amongst themselves, “Yes, it is possible to build this Trail if Canadians work together – but Canada is huge, so we’ll need all the help we can get.” Much of this help came from trail volunteers.

There is no doubt that, without the legions of trail volunteers, the TCT would have been just a pretty idea. The over 80 trail organizations and tens of thousands of volunteers spread out across the country have been crucial elements in the development and maintenance of the Trail.

The provincial/territorial trail and recreation associations that have partnered with the TCT have had an especially important role to play in the completion of the Trail, acting as intermediaries between the TCT and other regional and local trail organizations as well as landowners, governments, etc. Through their dedicated partnership, they have given the TCT a team of experienced trail advocates to work with and learn from.

And it is fair to say as well that all the trail volunteers inspired, and continue to inspire, governments, corporate sponsors, and members of the public to support the Trail. - To get the project approved, the Trans Canada Trail’s founders needed corporate support. Who were the TCT’s early sponsors? What did their support provide?

A bank (Canada Trust), a car company (Chrysler), a national distributor (Canada Post), a national television network (TSN/RDS), and an airline (Canadian Airlines) all came on board to help fund, advertise, and support the Trans Canada Trail as it gradually became established.

In addition to TSN/RDS, other media outlets provided support through free advertising and news articles. Newspapers across the country began to pick up Trail-related stories, and magazines such as Canadian Geographic and MacLean's provided features.

Other sponsors joined the Trail project on a smaller scale, and these too were important to the project’s success. - Was the Trans Canada Trail meant to be, or was it all just luck?

YES, the Trail definitely seemed meant to be, and YES, there was also quite a bit of luck involved.

The project was born because the Canada 125 team included a person (Bill Pratt) who loved to create legacy projects and who was in the right place at the right time to pursue the Trans Canada Trail idea. Those who worked with Pratt on the Trail had the feeling that the time had come to connect existing Canadian trails into a single, nation-wide trail – so, in a way, the project was meant to be, since it was supported by a determined team who saw it that way!

That said, although the team had lots of hope and were confident that the project had a good chance of success, they also needed luck. For example, they needed government support and seed money to get started on, and this support seemed highly uncertain all the way to the end of Canada 125. In fact, soon after Canada 125 wrapped up, support for the TCT was completely withdrawn (bad luck!) before being reinstated again (good luck!). Many more waves of good and bad fortune followed in the coming years. - You may already have seen the Trans Canada Trail logo while out for a walk, roll, wheel, ski, etc. What is the meaning of the logo? Who is the artist behind it?

You might say to yourself, “That’s the maple leaf!” This is true, but it's not quite so simple. The artist behind the logo said that, yes, his design was based on Canada’s national symbol the maple leaf. However, the logo also has its own meaning. What is it?

Way back in 1991, a logo contest took place for Canada 125. The winner of the contest was Halifax-based graphic artist Peter Gough. His logo was therefore attached to all the materials associated with the anniversary celebrations. Then, once the Trans Canada Trail was established, Gough's logo was adapted in order to represent the Trail but was coloured blue, yellow and green to reflect the natural world.

Gough’s interpretation of the Canada 125 logo that would later be adapted for the Trail is outlined in a 1992 article in the Halifax Chronicle Herald-Mail Star:The three prongs of the leaf depict three founding peoples – the native population, English and French as a combination, and immigrants from all areas of the world reflecting Canada’s multiculturalism.

[…]

“The three parts of the leaf also represent our past, present and future and depict West, the heartland and the East, ” said Mr. Gough.

They are joined together in one icon representing the culture mosaic, a community growing out of the vast expanse of one land, he said. - Why are there red-roofed pavilions all along the Trail?

To promote the Trans Canada Trail, a route drawn on a map of Canada was included in all the Trail’s promotional materials as a way of getting the public to imagine the scale and scope of the project. This was a great start, but it wasn’t enough to get people really engaged. Another idea was needed. What could it be?

“Selling metres” was the solution chosen by the founding team. Canadians would pay $36 to build a metre of the trail, and could buy as many metres as they wanted. In return, their names or the names of people they chose would be inscribed on pavilions along the route.

The metre-buying program gave members of the public a stake in the project. The program also created the buzz needed to help gain more support from governments, corporations, the media, etc.

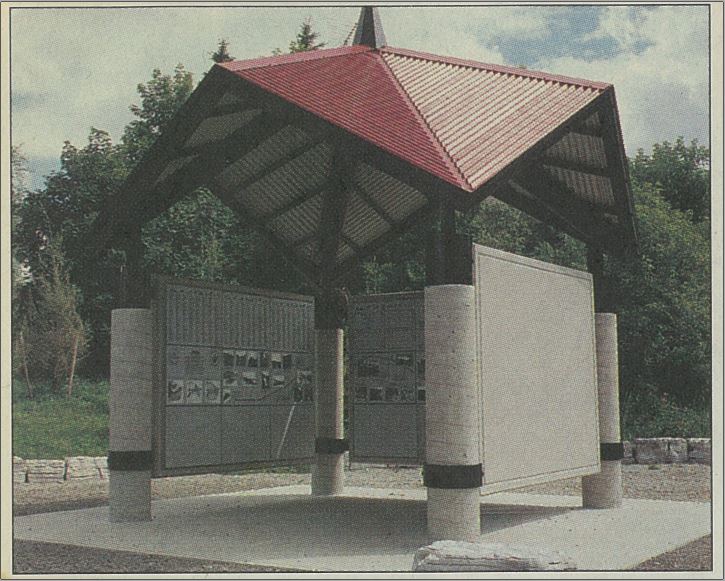

Selling metres led to the building of distinct, red-roofed pavilions across the country, creating visual reminders of the expanding national trail and of all the public support it was receiving.

The First Trans Canada Trail Pavilion in Caledon East, Ontario

(Trans Canada Trail 2.1 (October 1996)) - The TCT Foundation decided to build gateways at the borders between each province and/or territory. What was the first gateway? Why build these gateways?

The picture below shows the very first gateway, built between Québec and New Brunswick in 1997.

You know by now that the TCT was a legacy project to remember the 125th anniversary of the Canadian Confederation. Confederation was the process by which Canada was gradually comprised of its current provinces and territories, beginning with Ontario, Québec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick on July 1, 1867. The gateways link each province and territory – welcoming visitors!

- The Trans Canada Trail’s route is not the same as it was at the beginning. What are the main differences between the vision of the Trail route in the beginning and the actual route today?

There are quite a few differences. Here are a few of the main ones:

The original Trans Canada Trail route was 10,000 kilometres long, but now it is slated to be nearly 24,000 kilometres long once completed, so its length has more than doubled.

The Trans Canada Trail’s founders envisioned the Trail as a land-based path but, as of 2007, waterways were included in the route. Questions had arisen about the feasibility of a purely land-based approach. For example, how does a land-based path practically deal with the tangle of waterways through sparsely-populated northwestern Ontario?

When the TCT was launched, there was no territory of Nunavut, but in 1999 Canada’s Inuit people acquired their own territory. A Nunavut section of the Trans Canada Trail therefore had to be added, though it could not practically be attached to the rest of the Trail due to great distances and wide water barriers. The Nunavut section of the Trail, unattached to the rest of the route, stands as a symbolic inclusion, indicating the importance of the territory to a complete picture of Canada and of the Trans Canada Trail / The Great Trail.

An early plan for the TCT’s route through the north included a 350-odd kilometre stretch of the defunct World-War-II era Canol Road from the Yukon into the Northwest Territories. However, it was decided that this route would be too isolated and dangerous, so the Trail was re-routed to run parallel to the Alaska Highway from Alberta through British Columbia and into the Yukon, then along the Dempster Highway from the Yukon east into the Northwest Territories.

Along the way, the TCT also got longer and more complex, as many Canadians offered route suggestions and many Canadian communities asked to be connected to the Trail.

Over the years, there have been other significant changes to the Trail’s route, which people across Canada have been working hard to complete in time for the Canada 150 celebrations in 2017. - Why is the Trail's east-west route so far south?

The main answer to this question is simple: comparatively speaking, there just aren't very many people further north. In fact, 90% of Canadians live within 160 kilometres of the United States border. There are a few reasons for this. One simple reason is that it's generally warmer further south, and it's easier for most people to live where it's warmer.

Another reason involves history and trade. In the east, the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes provide a fantastic means of travel and transport, so the largest population centres in the east have been built along the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes – again, very near to the United States border. In fact, the river and the lakes helped determine where the border would be in the first place. It's also easier to transport goods to and from other countries if you are closer to them, and Canada's biggest trading partner is the United States.

Yet another reason why Canadians tend to live in the south is that much of the Canadian north is made up of dense boreal forest, bog, tundra, and mountain ranges, all of which make large-scale settlement challenging. - Why was the decision made in 1992 to extend the Trans Canada Trail north to the Yukon and the Northwest Territories?

The very first plans for the Trans Canada Trail did not include a northern route because, though vast, the region is sparsely populated. Building a trail from coast to coast was already a big task, and adding the north would add considerable difficulty to the task. However, at a Canada 125 board meeting in 1992, two territorial board members, Viola Campbell (from the Yukon) and Chief Cece McCauley (from the Northwest Territories) made a strong case for including their territories on the Trail’s route (in 1992, the current territory of Nunavut was still part of the Northwest Territories). Campbell’s and McCauley’s words made clear the value of such inclusion, not only for people in the north but for Canadians’ overall sense of Canada as a whole country, so a northern route was added to the plans.

Canada's north is home to many First Nations and Inuit communities as well as settler (descendants of Europeans and other immigrants) and mixed communities. The history of the north is long and rich, and today the north boasts a vibrant diversity of cultures along with important, resource-based economic activity such as mining, oil, and forestry. Though northern communities may be relatively small and spread out, they form an important part of the character of the country. For all these reasons, the northern route was a valuable addition to the Trail. - Why does the northern land route of the Trans Canada Trail go through Alberta and northern British Columbia instead of further east?

The two largest population centres in the Canadian north are also two of the territorial capitals. Whitehorse (Yukon), with a population of roughly 28,000, is north of British Columbia, and Yellowknife (Northwest Territories), with a population of about 19,000, is north of Alberta. Therefore, in order to reach as many Canadians as possible, as well as to reach all the Canadian capitals, it makes sense for the Trail to reach Whitehorse and Yellowknife.

There is also a practical advantage in following the edge of the Alaska Highway northwest toward the Yukon. The Alaska Highway is the only year-round road linking the Canadian south to the territories in the north, and it would be extremely difficult to maintain a forest trail across such great distances with so few available volunteers. Therefore, it made sense to create a Trail link from Edmonton to the Alaska Highway and then to continue north along the highway.

A further advantage of a route north through Alberta is the presence of the Mackenzie River. The river is an important historical trading route and is one of the Trans Canada Trail's water routes, acting as a twin to the northern land route. Also, due to the challenges of developing trails in the sparsely populated north, the land route from Yellowknife does not connect to the rest of the northern land route (which is much further west), but instead joins the northern water route just west of Great Slave Lake. - Which cities and towns does the Trail pass through?

The Trail connects around 1000 communities, and 80% of Canadians can reach it within a half-hour drive. It's not practical to list all the communities the Trail passes through, but we can at least provide a list of capitals and a few other major cities on the Trail's route:

In addition to Ottawa, Canada's national capital, the capital cities of every province and territory in Canada are included on the Trail's route:Provincial and Territorial Capitals

- Victoria, British Columbia

- Edmonton, Alberta

- Regina, Saskatchewan

- Winnipeg, Manitoba

- Toronto, Ontario

- Québec City, Québec

- Fredericton, New Brunswick

- Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island

- St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador

- Whitehorse, Yukon Territory

- Yellowknife, Northwest Territories

- Iqaluit, Nunavut

Along with the capitals, most other major centres across the country are on the Trail’s route. For instance, you can access the Trail in Vancouver, Calgary, Saskatoon, Toronto, and Montréal, in addition to countless other, smaller cities and towns across the country. To see all the cities and towns on the route, take a look at the “Explore the Map” section of the Great Trail website.

- Will all Canadian trails eventually join the Trans Canada Trail?

The short answer is “No.” For one thing, such comprehensive coverage has never been part of the Trans Canada Trail’s mission. For another thing, it's just not feasible. Though hundreds of different trails are incorporated into the route, and more trail organizations will undoubtedly decide to be part of the Trail, Canada's network of trails is too complex and diverse to be brought together under a single umbrella.

Before the Trans Canada Trail started in 1992, there were already a huge number of recreational trails all across Canada. This is what made the Trail idea seem possible in the first place. Now the Trans Canada Trail / The Great Trail is made up of over 500 individual trails, each with its own unique features.

Some of the trails that existed when the Trans Canada Trail was founded had unique, established identities of their own, and have therefore remained independent. In addition, many Canadian trails are single-use (hiking only, etc.), whereas the Trans Canada Trail's mission is to be multi-use wherever possible; therefore, many single-use trails have also remained separate. Other trails are predominantly used in ways that are inconsistent with the Trans Canada Trail’s mandate as it has evolved. For instance, many trails are favourites of ATV users or off-road motorcyclists. For all of these reasons, the Trans Canada Trail will remain a prominent part of a rich network of trails across the country, but has no ambition to join them all under its own umbrella.